Optimal Encoding

Data encoding is one of the necessary steps of the machine learning process. Before a model can be trained on data, the data needs to be transformed into a format proper to learning. Proper encoding doesn't just make the data readable by algorithms; it can significantly enhance the efficiency and accuracy of the learning process.

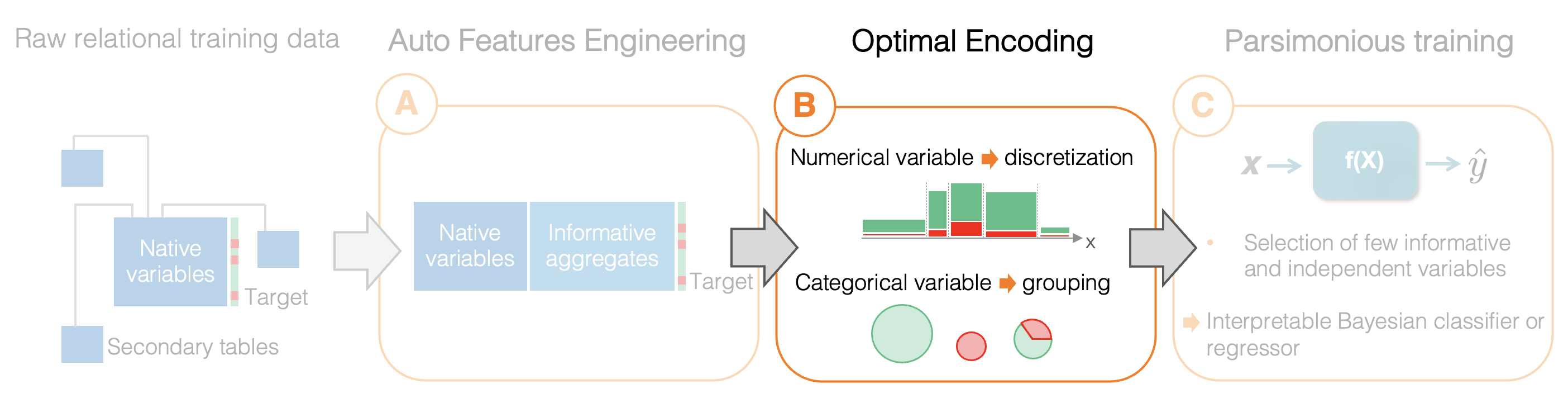

Khiops' Auto-ML pipeline recognizes this pivotal role of encoding and designates it as the second step (B):

In this crucial phase:

- Numerical variables go through an encoding process known as discretization which converts continuous variables into discrete ones;

- Categorical variables are further refined and encoded through a grouping method, which ensures their optimal categorization.

These transformations are not simply heuristic-based adjustments. The univariate models created at this stage become essential building blocks for the next stage of the pipeline, where they are selectively combined to form a parsimonious multivariate Bayesian classifier.

Recommendation

By exploring this section, readers will discover the details of encoding methodologies and grasp their technical advantages. However, to fully capture the nuances and principles of these techniques, it is recommended to first delve into the section "An original formalism", which introduces the MODL formalism.

The remainder of this page focuses on two primary sections: Discretization techniques and Modality Grouping methods.

Discretization

Building on the principles of the MODL formalism discussed in the Original Formalism section, this section elaborates on its application to univariate discretization. Univariate discretization transforms continuous variables into discrete intervals, which simplifies analysis and enhances model interpretability.

This section is divided into three main sub-sections:

- Model Parameters: Detailing the parameters and hierarchical organization of the models.

- Optimization Criterion: Understanding the Bayesian-driven criterion for selecting the most probable model.

- Optimization Algorithm: An overview of the optimization algorithm developed to train the discretization model.

Let's explore these aspects to gain a complete understanding of the MODL-based discretization process.

Model Parameters

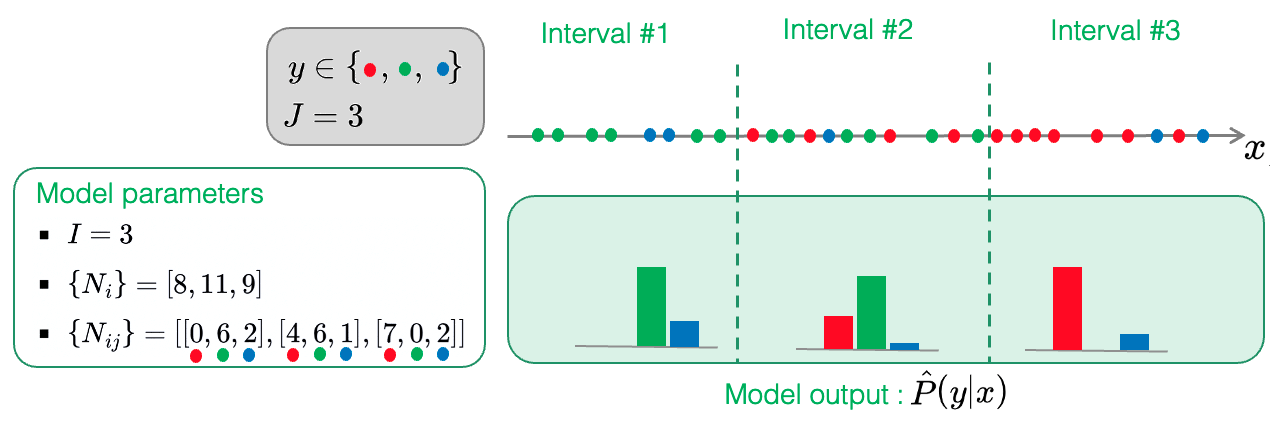

In the supervised context, discretization can be viewed as a univariate probabilistic classifier that aims to partition (or segment) numeric variable in order to describe the target variable distribution.

As previously introduced in the Original Formalism section, the initial step is the definition of the model parameters that are appropriate for the learning task at hand. This leads us to first define the family of hypotheses \(\mathcal{H}\). Within this family, each hypothesis \(h\) represents a unique way of segmenting or partitioning each numeric input variable into distinct intervals.

Once a numeric variable is partitioned according to a specific hypothesis, the resulting model behaves much like a probabilistic classifier. It estimates the class probability \(P(y|x)\) in an intuitive manner: for a particular numeric value \(x\), the associated probability \(P(y|x)\) of a class \(y\) is inferred by examining the distribution of classes in the interval containing \(x\).

In this context, a discretization model is uniquely described by the following parameters, organized into 3 hierarchical levels:

- \(I\): the number of intervals.

- \({ N_i}_{i \in [1, I]}\): the number of training examples in each of the \(I\) intervals.

- \({ N_{ij}}_{i \in [1, I], j \in [1, J]}\): the number of examples within each interval and belonging to each of the \(J\) classes.

It is crucial to notice two characteristics:

- Cardinality: The size of \(\mathcal{H}\) is directly influenced by the number of examples, denoted by \(N\), in our training dataset. Specifically, our first parameter \(I\), which denotes the number of intervals, can take any value between 1 and \(N\). This unusual property, where the model's possible configurations are tied to the size of the dataset, is atypical in a Bayesian context. As we will see later, this unique feature of the MODL approach has a significant impact on regularization (to prevent overfitting).

- Hierarchy: When defining a model, decisions are made in cascade across levels 1, 2, and 3; i.e., decisions made at an earlier level influence the number of possibilities at the subsequent level. Level 1 determines the number of intervals, which in level 2 drives the choices for positioning the \(I-1\) boundaries between the intervals within the \(N\) examples. Notably, MODL leverages rank statistics, using example counts in intervals to define interval boundaries. Lastly, level 3 summarizes the conditional distribution \(P(y|x)\), by specifying the class distributions within each interval that is defined by the boundaries set in Level 2. The number of available choices for this distribution is influenced by the parameters \({ I, { N_i}}\) from levels 1 and 2.

Optimization Criterion

MODL is a Bayesian model selection approach. The goal of the optimization criterion is to select the most probable model given the training data, denoted by \(d\). Based on what is introduced in the Original Formalism section and referring to information theory, the optimization criterion can be expressed as:

Given the model parameters introduced above, the optimization criterion used to select the most probable discretization model can be expressed as follows:

The prior:

It is hierarchical and uniform at each level of this hierarchy:

- level 1: probability of a particular number of intervals, all the values \(I \in [1, N]\) being equiprobable with a probability that equals \(1/N\);

- level 2: probability of a particular positioning of the bounds between intervals, given the value of \(I\), with \(\binom{N+I-1}{I-1}\) the number of possible positionings;

- level 3: probability of a particular class distribution within the interval, with \(\binom{N_i + J -1}{J-1}\) the number of possible such distributions.

As a reminder, the logarithm is used in this context to transform the probability product (from the Bayes formula) into a sum. Thus, the sum of levels 1, 2, and 3 finally expressed a product of independent probabilities corresponding to successive choices at each level.

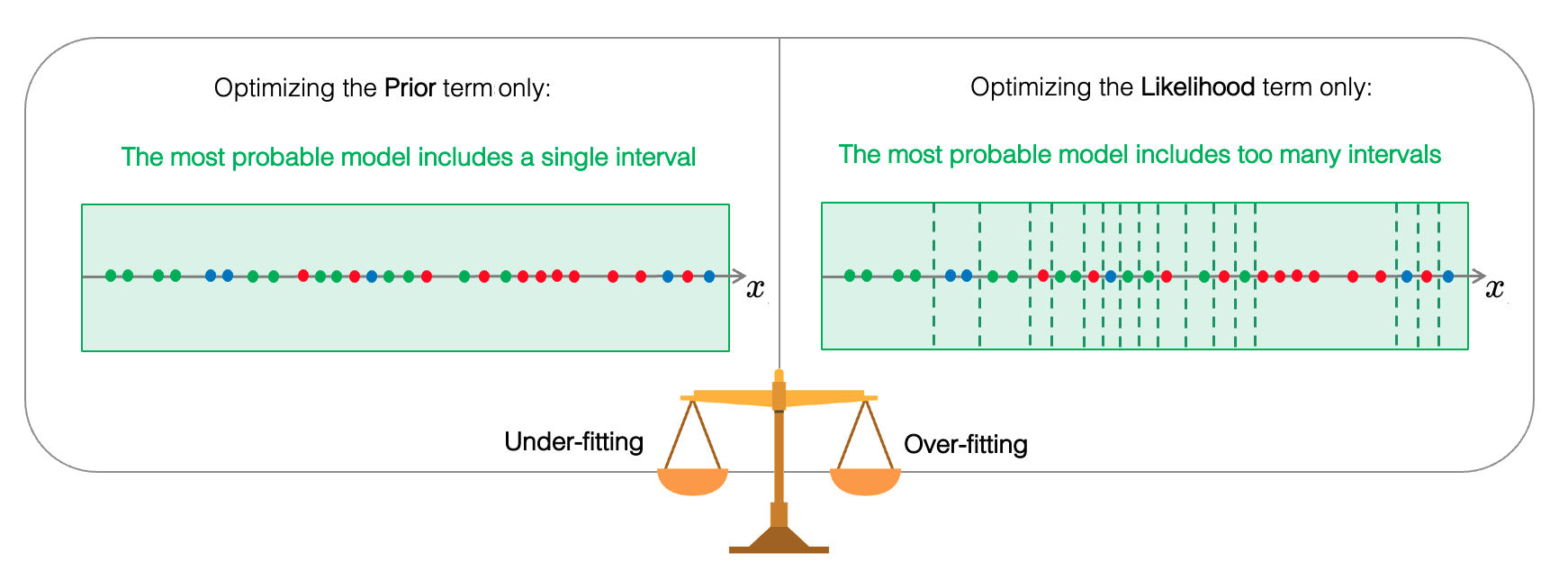

Also, it is important to notice that the prior evaluates hypotheses' probabilities from the combinatorial space of possible discretizations, regardless the training examples. Simple models (with fewer intervals) are promoted since an important number of intervals increases the number of possible positioning of boundaries and the possible class distribution within the intervals.

The Likelihood:

This term estimates the probability of a particular training set consistent with the model's description (i.e., given the parameters of the model), which turns out to be a multinomial problem. For each interval, the multinomial coefficient counts the number of distinct ways to permute the \({N_i}\) training examples (the dataset) where the number of examples \({N_{ij}}_{j \in [1, J]}\) of each of the \(J\) classes is known (the multiplicity). Optimizing the likelihood aims to create intervals that are as homogeneous (or pure) as possible, i.e., ideally containing only a single class.

There's a natural balance between the prior and the likelihood in this approach, preventing overfitting

While the particular shape of the prior distribution naturally leans towards models with fewer intervals, the likelihood tends to support more complex models that accurately describe the training data (i.e., more intervals). Given that both terms are consistent, there is no need to weigh one against the other. This inherent balance is what makes MODL hyperparameter-free.

In traditional machine learning approaches (see our section about classical Empirical Risk Minimization ), the weight of the regularization term depends on the size of the training set. As the training set grows, the weight attributed to the regularization term may be reduced, allowing the model to capture more accurate patterns in the data. Similarly, in the MODL approach, the balance between the prior and likelihood is natural and automatically adjusts the model's complexity based on the size of the training set.

As the size of the training dataset grows, the cardinality of \(\mathcal{H}\) also expands, offering a more significant number of ways to discretize the data into intervals. Thus, the combinatorial space of possible permutations becomes larger, thus making the likelihood term more consequential in the overall optimization process (the probability of a particular training set diminishes in this expanding space). Consequently, the prior term, which generally promotes simpler models, becomes less influential than the likelihood. This shift in balance leads to more accurate models, while maintaining robustness.

Optimization Algorithm

This section provides a high-level overview of the optimization algorithm utilized for discretization. For a more in-depth understanding, please consult the relevant scientific publications.

Given the exponential growth of the number of potential models relative to the dataset size, an exhaustive optimization approach is not feasible. While dynamic programming can provide an optimal solution for discretization, it may not be efficient enough. As a result, a heuristic-based algorithm is used instead. This method is significantly faster and produces models that closely approximate the optimal solution.

The algorithm operates in two distinct steps, as illustrated in the following figure:

-

Step 1 consists of a greedy algorithm which starts by evaluating the most complex model (single-value intervals), and iteratively performs the best merge (minimizing the MODL criterion) between two consecutive intervals, until the single-interval model is obtained. At the end of this run, the best model is kept for the next step.

-

Step 2 is a neighborhood exploration used to exit a local optimum, and which considers several types of transformations: (i) merging two intervals, (ii) splitting an interval, (iii) moving a bound, (iv) merging 3 intervals and splitting the result in two intervals. The best transformation is applied as long as it improves the model (i.e., it decreases the MODL criterion).

For an efficient coding, it is necessary to keep in memory the sorted lists of all possible transformations, ordered by the improvement of the optimization criteria. These lists must be updated for each transformation that is performed on the model.

Modality Grouping

Modality grouping operates as an essential mechanism for categorizing and simplifying categorical variables, thereby improving the efficiency and interpretability of subsequent analysis processes. This section is organized similarly to the discretization section, covering model parameters, optimization criteria, and the optimization algorithm.

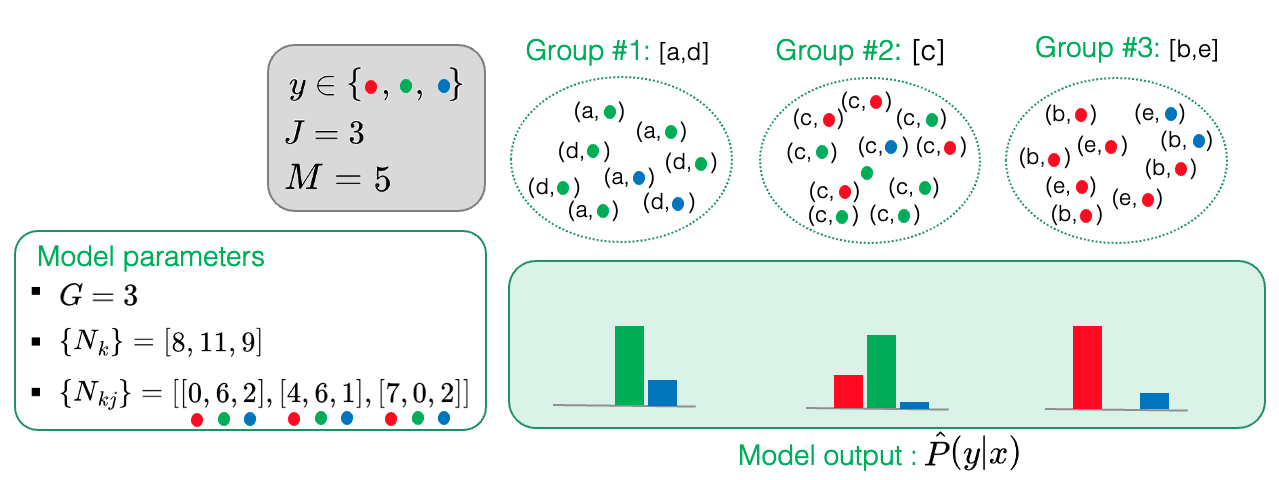

Model Parameters

In modality grouping, the goal is to optimally gather different modalities of a categorical variable in a manner that best predicts the target class variable. To introduce this concept, let us consider a categorical variable that has \(M=5\) different modalities, denoted by \(\{a, b, c, d, e\}\). In this setup, each training example is a pair \((x, y)\), where \(x\) is a modality and \(y\) is a class value (e.g., \((b,{\color{red} \bullet})\)). Just as for discretization, the goal is to find the most probable grouping model using the training data. This learned model estimates the conditional probabilities of class values \(y\) given observed modalities \(x\) by counting examples within each group.

A grouping model is uniquely described by the following parameters:

- \(G\): the number of modality groups;

- \(\{g(x)\}_{x \in [1, M]}\): the index that maps a modality \(x\) to its respective group;

- \(\{ N_g\}_{g \in [1, G]}\): the count of examples in each of the \(G\) groups;

- \(\{ N_{gj}\}_{g \in [1, G], j \in [1, J]}\): the count of examples in each group for each of the \(J\) classes.

Optimization Criterion

In a very similar way to the discretization, the following criterion must be minimized in order to select the most probable grouping model:

The prior

It has the same hierarchical and uniform shape as for discretization, but it differs slightly:

- level 1: probability of a particular number of groups, all the values \(G \in [1, M]\) being equiprobable,

- level 2: probability of a particular composition of groups, given the value of \(G\),

- level 3: probability of a particular class distribution given the previous parameters.

Unlike numerical variables, which can be arranged in a specific order, categorical variables have distinct values which cannot be inherently ranked. Consequently, the level 2 term in our optimization criterion enumerates the possible configurations for forming \(G\) groups from \(M\) distinct modalities. Specifically, this term quantifies the probability associated with a particular index function \(\{g(x)\}\), given a fixed number of groups \(G\). It assumes that all possible indexes are equally probable. The count of these possible configurations is determined by the sum of the Stirling numbers of the second kind, denoted as \(S(M,g)\).

For more details, you can refer to the scientific publications.

The likelihood

It is defined as previously discussed, i.e.:

Optimization Algorithm

The optimization algorithm used to train the grouping models is similar to the discretization case. In the same way, the number of possible grouping models increases exponentially with the number of modalities \(M\). For this reason, an exhaustive optimization algorithm is not feasible, as it would not scale. The algorithm used is a heuristic composed of two successive steps:

-

Step 1 consists of a greedy algorithm which starts by evaluating the most complex model, and iteratively performs the best merge between two groups, until the single-group model is obtained. At the end of this run, the best model is kept for the next step.

-

Step 2 is a neighborhood exploration which repeats the following two steps as long as the model is improved: (i) moving the modalities between groups, (ii) merging two groups.

For an efficient coding, it is necessary to keep in memory the sorted lists of all possible moves and merges, ordered by improvement of the optimization criteria. As before, these lists must be updated for each transformation performed on the model.

Summary of Technical Benefits

Optimal Encoding

Discretization and grouping models offer an ideal framework for encoding both numerical and categorical variables without requiring user-defined parameters. These supervised approaches become progressively more accurate as the volume of training data expands. Furthermore, Khiops can be seamlessly integrated into existing machine learning pipelines, thereby eliminating the need for arbitrary pre-encoding decisions or their inclusion in hyperparameter optimization.

Robust Evaluation via Compression Gain Metric

Khiops provides a robust metric called Compression Gain, also known as Level in Khiops outputs, that can be directly applied to training data for evaluation. In information theory, MODL optimization criteria represent a coding length, i.e. the number of bits needed (i) to describe the model (prior), (ii) to describe the target variable \(y\) of the training data (likelihood). Because this value is dependent on the dataset's size, it is not a standalone evaluation metric. The Compression Gain \(CG\) corrects for this by normalizing the learned model's \(\hat{h}\) coding length to a baseline model \(h_0\), which consists of a single group/interval:

Available in Khiops' output, the Compression Gain metric weighs the individual predictive level of each variable for the target \(y\), effectively measuring its importance.

Resilience to Outliers

Being based on rank statistics, the MODL approach ensures that outliers have no impact on the learning process for discretization models. Specifically, an extreme value is simply processed as the smallest or the largest value.

Data Cleaning Not Required

Khiops eliminates the need for cleaning your training data, and even discourages it to avoid introducing bias into the data. The library incorporates the missing values as predictive features rather than discarding them. In the case of discretization models, missing values are treated as an extreme value, while for modality grouping models, they are treated as a distinct modality. This enables the model to capture informative patterns the missing values might offer for classifying the target variable. During inference, any unknown modalities encountered are automatically categorized as missing values.